Interview with Virpi Suutari: “It’s important to be on your protagonist’s side, which doesn’t mean you need to flatter them all the time”

By Marta Bałaga

Virpi Suutari

In Aalto, acclaimed documentary filmmaker and Jussi winner Virpi Suutari takes a look at the famous Finnish architect and designer. But also at the many figures by his side, now finally getting their turn in the spotlight – including his wives.

When you decide to talk about someone so known, it generates interest. But it can be quite limiting sometimes, too. I recently saw a film about Salvatore Ferragamo and it was unwatchable. Everyone kept saying how wonderful this guy was!

It’s a crazy project in that sense – it’s almost impossible for it to succeed, because everyone has some sort of opinion about Alvar Aalto and the Aalto design. Lots of people really hate him! Others love him, so much that they want to protect him, claiming you shouldn’t say anything critical. Even society’s rejects have something to say about him, not to mention that almost every Finnish home has an Aalto object inside it. I couldn’t have done this film when I was younger, because you need to be independent. You need some life experience. I needed to be over 50 years old!

This wasn’t a commissioned work, although one could easily assume so. I wanted to make it because I come from Rovaniemi and where I grew up, there is a library designed by Aalto. It was designed in 1960s. I was there almost every afternoon after school and even as a child I had a feeling I was in a very special place. I was proud that I can almost “own” a part of it. It certainly left a mark inside and Aalto was one of the heroes of my childhood, because Rovaniemi was totally destroyed by the end of the war. After the war they rebuilt it very quickly, and it was very ugly. But then there was Aalto, and other architects, who came to its rescue and did wonderful things, some truly wonderful projects. When we were talking about our town, he was one of the heroes. I guess many Finns share the same experience.

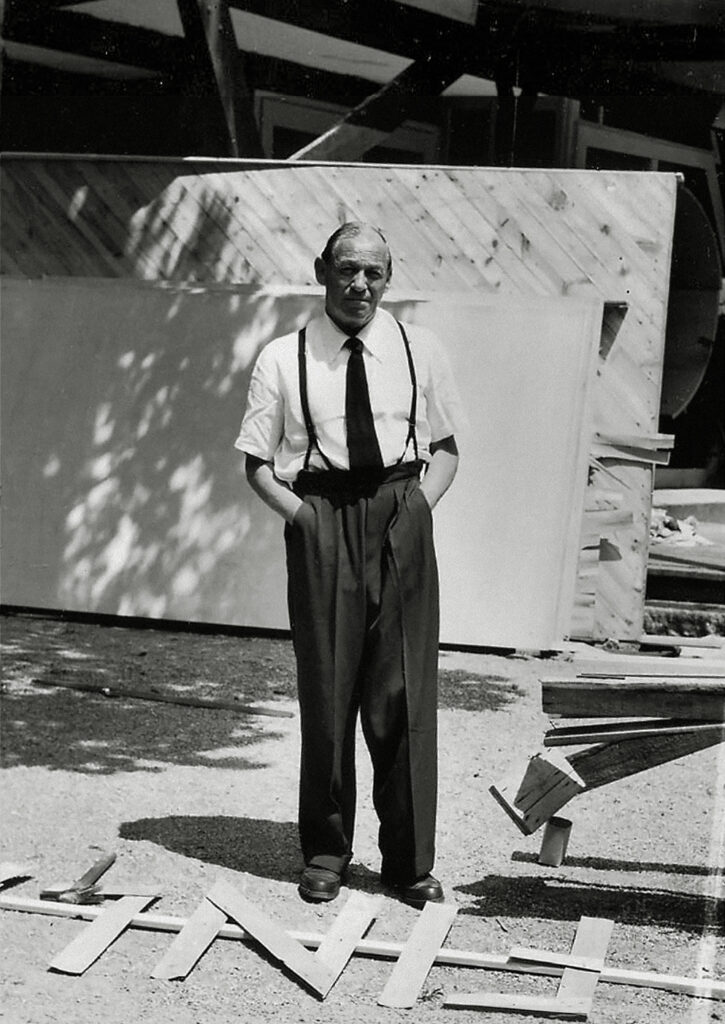

Alvar and Aino Aalto / copyright the Aalto family

And now you wanted to know more about the man?

Even now, as I grew older, I still don’t know my motives most of the time. I guess I wanted to know who he really was as a human being. Then of course I discovered that he wasn’t alone, that there was Aino, his first wife, who had a very significant role in creating the Aalto “grammar”, its vocabulary and its style – they developed it together. Then there was his second wife, Elissa, other architects working in the Aalto office, the carpenters, and wise, advanced clients like the Gullichsen family.

This project was important to me, also as a filmmaker, as I wanted to do something different. I wanted to develop my own skills, get more knowledge about that time. It was a very “civilizing” project for me, you could say, and aesthetically very different from my previous films. You can’t always do the same thing, the same film – it’s very important. You need to find new challenges for yourself. Of course it’s still very much my film, and there are always certain moods in them, but this was very different indeed.

We were all afraid how it will go, especially in these times, but the [local] theatrical release has been wonderful for a documentary. In Finland, it has been really tough to get the audience to watch documentaries in cinemas. Even though there is a long tradition of creative documentaries – they are so much more than just TV. I am so happy that the audience have found it. I also realized there is a need for this film. It wasn’t very difficult to get financing, as when I went to pitch it at IDFA Forum for example, TV commissioners said: “Ok, we were just thinking of having a film about Alvar Aalto. We went through our archives and there wasn’t anything, so we will take this film.” My intuition to make it met the intention of the buyers.

Which, I have to say, is extremely rare.

There has always been interest towards the Aaltos and their philosophy. It’s appreciated by the contemporary architects, like Shigeru Ban from Japan or Frank Gehry, who said that as a young man, he saw Alvar Aalto lecturing and was inspired to become an architect himself. They influenced so many people, but we don’t know that in Finland. Still, I realized early on that this film shouldn’t be just for Finns. I am happy it worked out for them, but I didn’t want to go too deep into some provincial Finnish societal issues. I challenged myself to combine the personal with the professional here – in most films about architecture, it’s usually either/or. I didn’t want to make a distanced, academic film, only with the buildings and a cool soundscape. I wanted to have this human side of the Aaltos as well. I was happy to see that this approach has worked also for the professionals, because so many researchers know Aalto’s work, but they haven’t got to know the personal side of it all.

Säynätsalo Town Hall / copyright Euphoria Film

When it comes to the personal side of the film, I could recognize your touch. You are a tender filmmaker – it was noticeable in your Garden Lovers, for example. But when you show relationships that are in the past, all you have are snippets of information. Or these letters, where Alvar talks about “Aino, who kisses me in smooth places.”

There is a lot of research material about them and books, and at first I had to study it all in order to interview the so-called “narrators” in the film. When I was doing that, I panicked – I realized the film can’t be just about this. I had to get closer to these protagonists that, yes, are already dead. It was a huge challenge: how to make this film alive? How to give it some oxygen? And how to get to know Aino, as there isn’t that much material about her at all?

I must say that at the beginning, I was quite puzzled. Then I reached out to the Aalto family and that was the key – I started believing in the film. It was a long process to get their trust, making them understand that I am a real filmmaker and I am serious about this. When you make films like this one, you need quite some time to get to know the right people and make them trust your project. The moment I got their permission to use the letters, the grandson brought many boxes of them and I started to read them with my assistant. Then I felt, for the first time, that I can make this film. I got to know Aino a little bit better, and the whole dialogue between them. I learnt about their relationship, its dynamics. I also got the family albums, because she was a wonderful photographer, influenced by László Moholy-Nagy.

I didn’t have any limitations as to how to use them, but I tried to be tender, as you said. I chose quotes that reflect something relevant, but they weren’t supposed to play too big of a role. Take this open sexuality for example, something they already had in the 1920s and 1930s. I wanted to use it a little, but not too much – same with Alvar’s alcoholism. It’s there, but I am not giving it too much space. You have to be sensitive about how to use this kind of intimate material. Their sexuality was important, as it tells something about these people. They wanted to be modern, in every aspect of their life, but it reflects this particular time, too. These were the pre-Sixties!

Alvar Aalto / copyright Isa Andrenius, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Still, this idea of an open relationship seems a bit one-sided in the film. It worked more for him than it did for her, at least judging from these exchanges.

You are absolutely right. As time went by, it became even more one-sided. Alvar’s personality was very extrovert, he wanted to charm everyone and have these adventures. Or at least he was talking about them – we don’t know if it was true or if it was just this image he wanted to create. Over the years, it caused some sorrow between them and Aino suffered because of that. When he realized she was going to die, he felt a lot of guilt. But it’s interesting to see in the letter how he is telling her to have her own erotic adventures, saying: “I don’t love you as a moral creature but as a human being”. It’s almost as if he was writing to himself, saying these things to himself.

Also, their letters are extremely beautifully written, there is a lot of humor and warmth. Without them, I would be in big trouble. You know, there is a 52-minute-long TV version of that film for some countries and the letters are not in that version. It works in its own way, as a more informative film, but it’s lacking that aspect. They give this film its heart.

I am always afraid of the “talking heads” in documentaries, but you found a way to deal with that by having this cacophony of different voices. You hear the experts but you don’t see them, and you can focus on the story instead.

That was the idea from the beginning. For the TV versions we filmed all the interviews, so we have the material. But we decided not to use it. It would have taken so much time away from the actual content and it’s not so relevant, actually, to know who is talking. In Aalto’s case, there are tens of researchers who have concentrated on very specific things: someone knows about the churches, someone about the libraries and so on. I have done this work for the viewer and created a web of narrators. We only made captions for those speakers who are first-hand witnesses, who have actually been there with the Aaltos. I know that for some it might be annoying not to know, because the convention is so strong. But even some researchers were happy about it. This way, you can just concentrate on the film.

Also because the role of the music and sound design is also important in my work, it creates a certain mood and viewpoint. I am always very engaged in these processes – I also studied music when I was young. When I start, at the point when I am only just dreaming about a certain film, I usually have a certain instrument or instruments in my head. In Elegance [a short film about, according to one festival, “Finnish gentlemen hunters”] it was the flute and the harpsichord, but used more as percussion, and in Aalto I thought about drums, piano and trumpet.

In Aalto, the role of music and sound design was especially significant in order to create a vivid and “flowing” atmosphere and narration, as there is this danger of coming off as “dusty” and stiff when the protagonists have passed away and other protagonists are design objects and buildings. We tried to create connections between the sound and the mind, awakening memories in the viewer and so on.

Vyborg Library Hall / copyright Euphoria Film

You show someone who “sees” things. When Aalto designs a sanatorium, he talks about designing it for a “horizontal person”. Would you say you are interested in people driven by some kind of obsession? Be it business ideas, like in Entrepreneur, gardening or hunting?

Maybe you are right about that. As for Garden Lovers and Elegance, what was interesting was setting the stage where people can act. The garden was kind of a painting – it framed their life. It was the same thing with hunting. They were obsessed, so it was easy to approach these people – after all, it was something they loved to do. And after that, you can talk about anything really: pose big questions about life and death and so on. For me, this stage where life happens has always been extremely important. I have used a lot of wide shots in my films because the landscape, the place, the space have always been crucial. Maybe Aalto was important also because I could explore it?

In Entrepreneur [about two food start-ups], I chose my protagonists also accordingly to the spaces. They are almost equally important. When I do casting, I think about the landscape and its possibilities. In that film, when I went to meet this family, at first it felt like a shabby little village, very uninteresting. But when you start looking at it more carefully, there are so many layers to that place where these people “act” and where life happens for them. It’s important to explore the possibilities of the landscape, always.

You are not interested in mockery. Which would be easy when talking about obsessions of any kind – it would be easy to play it for the laughs. And yet it’s never the case with your films.

I am really happy you would say that, because I have been accused of it in the past. Not very often, but some people thought there is too much humor towards the protagonists. I guess it tells more about the viewer, as one should see life as a comical landscape, I think. There are some moments of levity when people lose their dignity for a while. But what’s important is that when the film ends, the person gets their dignity back.

It’s important to see this other side of human beings. That’s the way I mostly look at myself and my family. If people think it’s a mockery, it says something about them I guess, but this tender kind of humor always exists in my films. With a wide shot, it can be seen more clearly – you notice how a person interacts or is in dialogue with their surroundings. One of the masters of that is Sweden’s Roy Andersson, who was one of the inspirations for me at the beginning of the 1990s. I also met him a couple of times. It’s important to be on your protagonist’s side. Which doesn’t mean you need to flatter them all the time! You have to be as honest as you can, but it’s always my interpretation of them and their lives. I also like to engage them, so that they can co-create the film a bit. The man in the Entrepreneur, he started to write about his life from a filmmaker’s point of view, suggesting what we should film. He was very engaged in the process. As for the ladies, they didn’t have any time for that – after all, they were in the middle of a start-up business!

Thinking about what you said about people’s surroundings, what you have in the background can also show who you really are, despite all your ambitious declarations and plans. It certainly seems so in the Entrepreneur?

These kinds of clashes, or a dialogue between what is being said and what you see is actually very interesting. I like to say about my aesthetic – although Aalto is a very different story – that it’s a “compressed reality”. I make careful research, I meet these people a lot before the actual shoot, I get to know what is normally happening in their life. I plan, but when the camera is rolling there is still enough room for spontaneous surprises. I am not so interested in the naturalistic type of cinema, I don’t want to document everything. I am thinking: What is relevant? What is interesting? How are political decisions and social realities of society reflected in these concrete lives? As a result, I don’t have that much material coming into the edition room. I have already made quite a few decisions beforehand.

If you think about paintings for example, Lucian Freud, one of my favorites, always exaggerated the hands or the marks left on the faces of his protagonists. In documentaries, you also have to see what is relevant and what is not. You have to abstract and exaggerate in order to make the essence of the thing more clear, because you are trying to tell a bigger truth. In Japanese landscape painting you see something in the front and then there is a lot that you can’t see. It’s called “the borrowed landscape” I think. I think that paintings or photography, which I used to study, inspire me much more than other documentaries. I always talk about paintings with my cinematographer before the film shoot.

Just like in the case of Roy Andersson! Whenever he is promoting a new film, he tends to talk about some specific painting that he had in mind. Usually by Otto Dix or Georg Scholz.

He didn’t tell me that in the 1990s! [laughter] [Finnish artist] Anna Tuori made these very interesting , multi-layered landscapes and they were important references when we were making Garden Lovers. This naturalistic, getting-everything-in-the-film approach is just not that interesting for me.

Sometimes I have been accused that my films were too “fictional” – just because everything is so clear and so compressed. I don’t see it this way. It’s still about people’s lives, it’s just constructed differently. I am allergic to scenes where protagonists are talking about their opinions about their life. It’s very common in reality TV for example – people talk about how they feel all the time and some think that’s what’s real. But what people say has more to do with what they are trying to hide. In my films, I am more interested in the reality that’s not immediately there. We always pretend to be more rational creatures than we actually are and I am also interested in that irrational side. I want to look at it in a tender way. Honest, but tender.

It’s funny how ridiculous we can be. Even with Aalto, everyone calls him a genius but you also show him moulding his second wife a bit like in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

We noticed that in the editing. “It’s like Vertigo!” You can be a great man, but you are also human. He didn’t really do anything terrible. It wasn’t very nice, but she agreed to that as well and we don’t know for sure whose idea it was. I am certain she got a lot out of this relationship. But yes, they even changed her name! She was Elsa, and it wasn’t fancy enough. It’s important to show these different sides of a person.

Main image: Maison Louis Carré, France / Copyright Euphoria Film